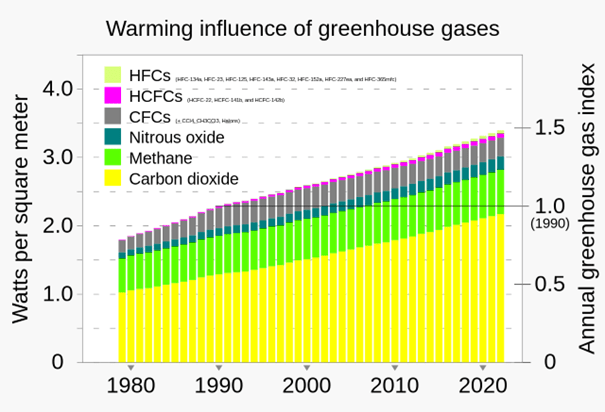

💌 Thanks to the continuous efforts of the United Nations since 1949 and the dedication of Green Parties worldwide, there has been a growing awareness of the ongoing climate crisis and the increasing global emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. This awareness has become particularly evident in traditional markets ranging from pork bellies to gold. It is becoming increasingly clear that sustainable and prudent economic management has been neglected.

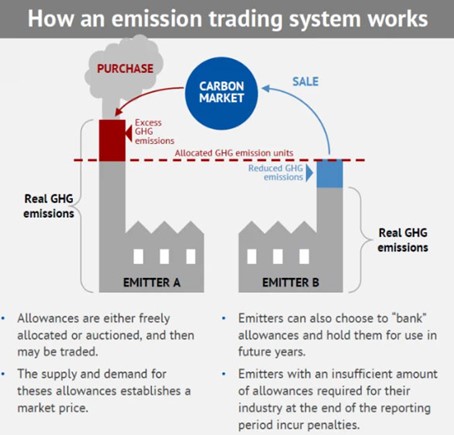

🕳️ This realization is particularly underscored by the fact that capital has seemingly escaped unnoticed through leaks in the financial system (figuratively through an unnoticed hole in the wallet), leading to the emergence of a quasi-independent economic ecosystem at ground level (actually clouds above us). In response, a dedicated carbon market (Emissions Trading System, ETS) has been established, allowing investors and companies to simultaneously trade carbon credits and carbon offsets.

🎮 The 1980s: An Era of Love, Joy, and the Debt-Nature Exchange – ELI5

In 1984, Mr. Lovejoy conceived an idea to help protect our environment. Some countries were burdened with substantial debt, while other nations wanted to assist but were uncertain how to do so. The solution they devised was akin to a barter system. The indebted countries pledged to safeguard their natural environments, and in return, other countries agreed to take on a portion of their debt.

While this is a wonderful plan, many wondered where the business aspect fit in, echoing Heinrich Böll’s quote: „The only threat that truly frightens a German (and not just Germans) is the threat of declining sales.“

🈺 🥐 The Kyoto Protocol of 1997 and the Paris Agreement of 2015 are international treaties that establish CO2 emission targets at a global level. The Paris Agreement, ratified by nearly all countries, sets forth national emission targets and corresponding regulations.

An event that sparked outrage was President Trump’s highly publicized announcement in 2017 of the United States‘ intention to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. However, at that time, such a step was not immediately feasible due to a contractual waiting period of three years. It wasn’t until November 2020 that the United States officially withdrew from the Paris Agreement. However, this status changed by January 2021, as President Biden reinstated the country’s participation on his first day in office. In stark contrast, the United States had previously withdrawn from the Kyoto Protocol during President Bush’s tenure and has not re-entered it since.

In general, it can be observed that the Kyoto Protocol appears to have many unfilled columns, so to speak—significant gaps in its implementation. A key distinction between the two agreements lies in the fact that the Kyoto Protocol focused on developed countries, whereas the Paris Agreement applies to all nations equally. Apparently, the United States felt inadequately developed in the context of the Kyoto Protocol. While a discerning observer may assume that the country is now back on board with the Paris Agreement, it should be noted that the Paris Agreement lacks legal binding force, unlike the Kyoto Protocol, which constituted a legal obligation for all signatory parties.

The Kyoto Protocol was the wrong solution at the right time—a flawed attempt. Then came the Paris Agreement. The Paris Agreement is akin to ordering a family pizza, where everyone wants different toppings and styles (stone oven, Chicago, pan pizza, New York-style, or perhaps Neapolitan)—it’s easier to build a rocket to Mars than to come to a consensus

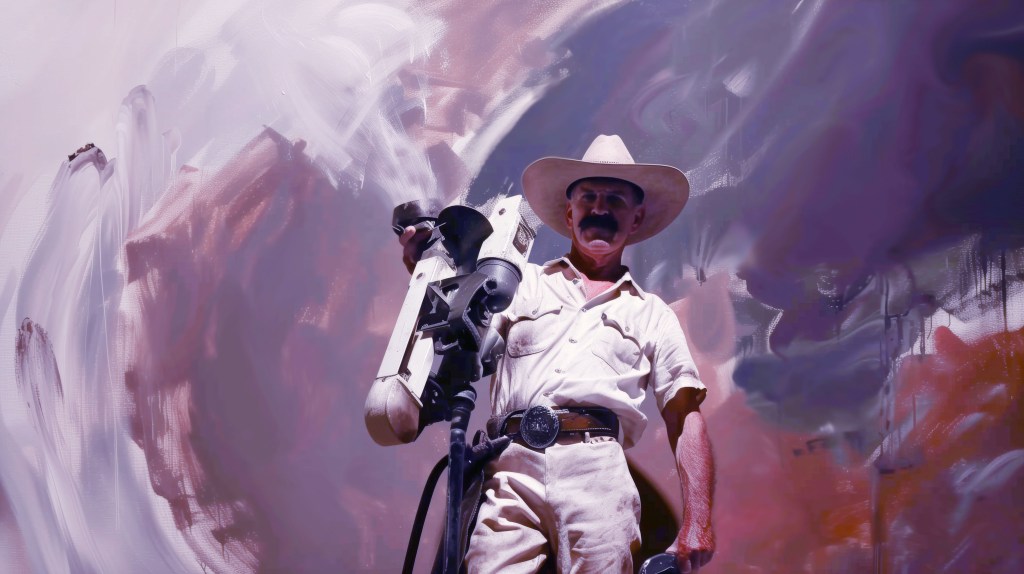

🤠 While Lovejoy may now wear a different hat, he’s still in the game. If we continue down this path, we’re essentially expanding the Geneva Convention to define environmental catastrophes as weapons against ourselves. As far-fetched as it may seem, the notion isn’t entirely implausible, given that Switzerland is the first nation to be urged by the European Court of Human Rights to take action.

🤼♀️ To me, the environmental aspect is like a vast ecological buffet, encompassing not only interstate relations but also a plethora of direct personal interactions—it’s practically like a nature party with all sorts of creatures!

Currently, this interpersonal environmental factor is dividing into a polarized dynamic between „woke“ and „unwoke“ (or anti-woke culture), which manifests itself in heated confrontations („shitstorms“), akin to environmental disasters. Recently, as I exited a drugstore in the pedestrian zone of Baden, I encountered a visibly agitated, somewhat disheveled woman with a distinct Austrian accent, loudly repeating the same words like a mantra: „They’re shooting directly at me. They’re shooting with words.“ She hurried past me with purpose. „She’s right, and she’s in the right,“ I thought to myself.

🏷️ The price and unit

A literal ton of carbon emissions, referred to as CO2e emissions, falls into one of two categories: carbon credits or carbon offsets, both of which can be bought and sold on a carbon market established as an interim (Note: Interim“ typically means „temporary“ or „in-between; in-between to what) solution. It’s a straightforward concept that offers a market-based solution to a complex problem.

👣 a) Carbon credits (regulatory compliance market), also known as emission permits, function as authorization certificates for emissions. When a company purchases a carbon credit, typically from the government (the European Union Emissions Trading System (ETS) allows companies to buy carbon credits from other companies as well), it receives permission to emit one tonne of CO2. With carbon credits, the revenue from carbon flows vertically from companies to regulatory authorities, although companies with excess credits can sell them to other companies.

How are carbon credits generated? Many different types of companies can generate and sell carbon credits by reducing, capturing, and storing emissions through various processes.

The global compliance market for carbon credits is massive. The total market capitalization is $261 billion (the EU carbon market is the largest, with approximately 50 billion euros in value (2023)), representing 10.3 gigatons of CO2 equivalent traded on compliance markets in 2020.

b) Carbon offsets (Voluntary Carbon Market, VCM) flow horizontally, facilitating carbon revenue trading between companies. When a company removes a unit of carbon from the atmosphere (for example, by planting more trees or investing in renewable energy) as part of its regular business operations, it can generate a carbon offset. The purchase of these offsets is voluntary. Other companies can then buy these offsets from the originating company to reduce their carbon footprint, or the originating company itself can further reduce the measurable amount of CO2e it emits.

The voluntary carbon market is challenging to measure. The costs of carbon credits vary, especially for carbon offsets, as their value is closely tied to the perceived quality of the issuing company. Third-party validators add a layer of oversight to the process, ensuring that each carbon offset genuinely results from real emissions reductions. However, even then, there are often differences between various types of carbon offsets.

While the voluntary carbon market was estimated at around $400 million last year, experts project the sector’s value to reach between $10 and $25 billion by 2030, depending on how aggressively countries around the world pursue their climate goals. Even with an optimistic growth trajectory, the voluntary carbon market would still significantly lag behind the required investment amount to fully achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement.

The voluntary carbon market is the arena where many companies, such as Apple, Stripe, Shell, and British Petroleum, are actively striving to offset their footprint. It is the sector with the most growth potential.

Carbon offset projects include, among others, renewable energy projects, improving energy efficiency, carbon and methane capture and storage, land use and afforestation, as well as simple everyday changes such as replacing household light bulbs from incandescent to LED bulbs.

Methane is easier to manage as it can be simply burned to produce CO2. While this might sound counterproductive at first, considering methane is over 20 times more harmful to the atmosphere than CO2, converting one molecule of methane into one molecule of CO2 through combustion reduces the net emissions by over 95%.

For carbon, capture often occurs directly at the source, such as in power plants. While injecting this captured carbon underground has been used for decades for various purposes like enhanced oil recovery, the idea of storing this carbon long-term and treating it akin to radioactive waste is a newer concept.

Land use and reforestation projects harness the natural carbon sinks of trees and soil to absorb carbon from the atmosphere. This includes the protection and restoration of old forests, the creation of new forests, and soil management. Plants convert CO2 from the atmosphere into organic matter through photosynthesis, which eventually ends up as dead plant matter in the soil. Once absorbed, the CO2-enriched soil helps restore the natural properties of the soil, improving crop production and reducing pollution.

While not an exhaustive list, here are some popular practices typically considered as offset projects:

- Investment in renewable energy involves financing projects for wind, water, geothermal, and solar power generation or transitioning to such sources wherever feasible.

- Improving energy efficiency globally includes initiatives such as providing more efficient cooking stoves for people in rural or impoverished regions.

- Carbon capture from the atmosphere and its utilization in the production of biofuels render them a carbon-neutral source of energy.

- Returning biomass to the soil as mulch post-harvest instead of removing or burning it. This practice reduces surface evaporation and helps conserve water. Additionally, biomass nourishes soil microbes and earthworms, facilitating nutrient cycling and enhancing soil structure.

- Promoting forest growth through tree planting and reforestation projects.

- Transitioning to alternative fuel types like lower-carbon biofuels such as maize-based ethanol and biodiesel derived from biomass.

If you’re curious about how carbon offset and allocation levels are assessed and determined through these processes, take a deep breath. Monitoring emissions and reductions can be a challenge even for seasoned professionals.

📈 The markets

The renewed interest in carbon markets is relatively recent. There are currently 25 different emissions trading systems worldwide, with 22 more in the planning stages. International carbon trading markets have been in existence since the Kyoto Protocol of 1997, but the emergence of new regional markets has sparked a veritable investment boom. The EU stands as a global leader in emissions trading, with member states having implemented the system as early as 2005 (today it covers approximately 40 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions in the EU). In the United States, there is no national carbon market, and only two states – California and Oregon – have a formal emissions trading system. However, concerning California, nine states on the East Coast have formed their own emissions trading conglomerate, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative.

🧢 California issues credits to residents for their gasoline and electricity consumption. (The average American generates 16 tons of CO2e annually through activities such as driving, shopping, using electricity and gas at home, and generally going about daily life.) The number of credits issued each year typically aligns with emissions targets. Credits are often issued as part of a „Cap-and-Trade“ program (a regulated market). Regulatory authorities establish a cap on carbon emissions – the „cap.“ This cap is gradually lowered over time, making it increasingly challenging for companies to stay within this limit. „Cap-and-Trade“ programs exist in some form around the world, including in Canada, the EU, the United Kingdom, China, New Zealand, Japan, and South Korea, with many more countries and states considering implementation.

Baseline credit systems operate on a similar process, but in reverse. Carbon credits are distributed only to companies that keep their emissions below a predetermined baseline level. These credits can then be traded with companies that exceed the baseline level.

Most major companies are doing their part and either are or have announced a roadmap to minimize their carbon footprint. However, the number of carbon credits allocated to them each year (based on the size of each company and the efficiency of their operations compared to industry benchmarks) may not be sufficient to meet their needs.

Despite technological advancements, some companies are still years away from significantly reducing their emissions. However, they must continue to offer goods and services to generate the funds needed to improve the carbon footprint of their operations.

Despite the challenges, analysts agree that participation in the voluntary carbon market is rapidly growing. However, even with the growth rate outlined above, the voluntary carbon market would still significantly lag behind the required investment amount to fully achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

Consumers are increasingly aware of the importance of carbon emissions. Consequently, they are becoming more critical of companies that do not take climate change seriously. By contributing to carbon offset projects, companies signal to consumers and investors that they are not merely paying lip service to the fight against climate change. For many companies, the corporate social responsibility benefits often outweigh the actual costs of offsetting.

Not every carbon credit market is equal, and it’s easy to find shortcomings even in tightly regulated programs like California’s. Carbon allowances in these markets may indeed not be as valuable as they claim to be, but since participation is mandatory, it’s difficult for companies to control their own impact.

In theory, purchasing carbon offset measures provides companies with a more tangible way to reduce their carbon footprint. After all, carbon credits only address future emissions. However, carbon offset measures allow companies to immediately address their historical CO2e emissions as well. Companies can also choose the types of projects that have the greatest impact, such as Blue Carbon projects. When applied correctly, carbon offset measures are a way for companies to earn additional PR points and achieve a more measurable reduction in carbon emissions. With no regulatory body overseeing carbon offset measures, standards organizations like Verra have become influential in monitoring the carbon offset market.

The Advantage of Offsetting

New Revenue Streams. There’s another significant advantage of carbon offset measures. If you’re the company selling them, they can be a major revenue source! The best example of this is Tesla. Yes, that Tesla, the electric car manufacturer, which sold carbon credits to established automakers worth $518 million in the first quarter of 2021.

That’s a massive deal and keeps Tesla alone from running into the red. If the carbon credit market continues to rise and certificate prices keep increasing, Tesla and other environmentally friendly companies could make enormous profits.

Do carbon offset measures actually reduce emissions?

Both offset measures and certificates don’t always work as intended. Voluntary carbon offset measures rely on a clear connection between the activity conducted and the positive environmental impact.

Sometimes, this connection is obvious – companies utilizing carbon capture technologies to remove and store CO2 emissions can point to concrete figures.

Other programs, such as initiatives promoting green tourism or offsetting the impacts of international travel, may be more challenging to measure. The reputation of the organization issuing the certificate determines the value of the offset. Reputable carbon offset organizations carefully select carbon projects and report on them diligently, while third-party auditors can ensure that such projects adhere to strict standards as set by the UN Clean Development Mechanism. Once properly vetted, „high-quality“ offset measures represent tangible, measurable amounts of CO2e emission reductions that companies can utilize as if they had actually reduced their own greenhouse gas emissions. Though the company hasn’t yet physically reduced its own emissions, the world is just as well off as if the company had already done so. In this way, the company has bought itself more time to make its operations more environmentally friendly while already appearing to have done so for the atmosphere.

Can you, as an individual, purchase carbon offset measures?

If you’re not representing a large company, it’s unlikely that you can directly purchase carbon offset measures from the source company. At least not at the moment.

Instead, you’ll need to turn to a growing number of third-party companies that act as intermediaries. While this may seem like an additional step, these companies offer some advantages.

The best companies also serve as a verification mechanism. They audit and verify to ensure that the carbon offset measures you’re purchasing actually offset carbon.

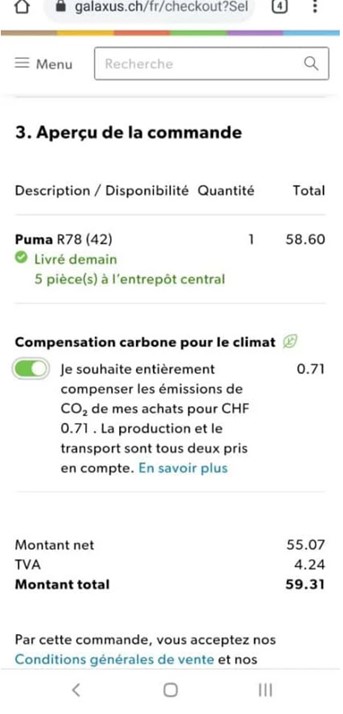

For example: Companies like Galaxus, Switzerland’s largest online retailer, offer consumers the opportunity to offset the carbon footprint of their purchases.

If this seems like they are trying to sell the holes in Swiss cheese separately to you as an individual/end user/consumer, then please bear with me for a few more lines.

Many organizations also provide a carbon footprint calculator. You can use these calculators to determine exactly how many carbon offset measures you need to be carbon neutral.

Ambitious organizations, companies, and individuals can purchase carbon offset measures to achieve net-zero or even nullify all previous historical emissions. For example, the software company Microsoft (MSFT) has committed to being carbon negative by 2030 and removing all carbon emissions emitted by them since their inception by 2050.

So, what do you need?

If you’re a company, the answer might simply be „both“ – but it all depends on your business goals as well as the local regulations under which your company operates. If you’re a consumer, carbon certificates may not be available to you, but you can still contribute by purchasing carbon offset measures.

Our crucial global goal is to both cease metaphorical chemicals from flowing into the water supply and clean up the existing water supply over time. In other words, we need to drastically reduce CO2 emissions and also work on removing the CO2 currently present in the atmosphere if we want to materially reduce pollution.

Why should I purchase carbon certificates?

If you’re a company, there are many compelling reasons why you should seriously consider investing in carbon certificates and offset measures.

If you’re an individual looking to purchase carbon certificates, you’re likely interested for one of two reasons:

The first reason is that you’re environmentally conscious and want to contribute to combating climate change by offsetting your own greenhouse gas emissions or those of your family.

If that’s the case, you can rest assured – carbon offset measures from a reputable provider like Native Energy are the perfect way for you to offset your own carbon footprint.

The second reason you may be interested in purchasing carbon certificates is that you see it as an investment opportunity. The global carbon market grew by 20% last year, and this strong growth is expected to continue as climate change becomes increasingly relevant to the world.

What is Blue Carbon?

Blue Carbon refers to specific carbon certificates originating from locations known as Blue Carbon ecosystems. These ecosystems mainly include marine forests such as tidal marshes, mangrove forests, and seagrass beds.

Yes, forests can grow in the ocean! Examples of this are the mangrove forests in marine bays, such as those in Magdalena Bay in Baja California Sur, Mexico.

Mangroves are trees (about 70 percent underwater, 30 percent above water) that have evolved to survive in flooded coastal environments where seawater meets freshwater, and the resulting lack of oxygen makes life impossible for other plants.

Key fact: Mangroves cover only 0.1% of the Earth’s surface. Mangrove trees provide shelter and food for numerous species such as sharks, whales, and sea turtles. And thanks to their other indirect effects like the positive impacts on corals, algae, and marine biodiversity, which have been severely impacted by activities such as overfishing and agriculture, mangroves are considered extremely valuable marine ecosystems.

Over the past decade, scientists have found that Blue Carbon ecosystems like these mangrove forests are among the most intensive carbon sinks in the world.

According to scientific studies, mangroves can store up to 4 times more carbon pound for pound than terrestrial forests.

This means that Blue Carbon offset measures can remove vast amounts of greenhouse gases relative to the area they occupy. Additionally, they also provide a plethora of other benefits to their local ecosystems.

As a result, carbon offset measures for Blue Carbon projects are traded at a premium price.

Additional Resources:

- https://www.fortomorrow.eu/de/blog/co2-ausgleichen-ueber-europaeischen-emissionshandel

- https://www.emissionshandelsregister.at/service

- https://www.emissionshaendler.com/de, https://carboncredits.com/carbon-stocks/

- https://carboncredits.com/the-ultimate-guide-to-understanding-carbon-credits

- https://carboncredits.com/top-4-carbon-stocks-to-watch-2023

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/dec/05/carbon-dioxide-co2-capture-utilisation-products-vodka-jet-fuel-protein

- https://www.greenfacts.org/images/foldouts-pdf/co2-storage-en.pdf

This post will continue either within this blog or as a standalone entry. Preview: The ongoing, yet unsustainable silver rush for solar panels – a treasure in the silver lake?

Hinterlasse eine Antwort zu CO2 Investments for Beginners: Addressing the Pain Point – 2024 Antwort abbrechen